The variola major virus is the causative agent for the deadly disease we know as smallpox. Thanks to successful global vaccination efforts spearheaded by the World Health Organization (WHO) after the last naturally occurring outbreak in the United States in the late 1940s, smallpox has since been eradicated. This eradication marked the first and only successful elimination of a human disease in the world. The last known naturally occurring case of smallpox was in Somalia in 1977. Since then, a confined/limited outbreak was reported in Birmingham, England in 1978 originating from a laboratory accident, killing one person. The disease was declared eradicated in 1979 and remains eliminated today. However, the viable virus remains in two known high security laboratories – the WHO Collaborating Centre on Smallpox and other poxvirus infections at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, and at the WHO Collaborating Centre for Orthopoxvirus Diagnosis and Repository for Variola Virus Strains and DNA at the Russian State Research Centre of Virology and Biotechnology in Koltsovo, Russia.

In response to the 9/11 attacks in 2001 as well as the Anthrax spore terrorism incidents, there has been an increased concern as viruses have been used as bioterrorism weapons. The smallpox virus is still regarded as a lethal bioterrorism agent; hopefully never to be unleashed considering that most of the population is susceptible to the disease due to the discontinuation of routine smallpox vaccinations over 40 years ago. Moreover, the smallpox virus is highly contagious, with humans serving as the only known host. If infected, the mortality rate is estimated to be about 30%, with up to 80% of survivors disfigured with the characteristic “pockmarks” on the face and body (deep-pitted scars observed during infection) and/or left completely blind.

Although the origin of smallpox is unknown, recent analysis of three separate 3,000 year old mummies of the Pharaoh Ramses V indicated smallpox-like pustules on the head of the mummies. Worldwide documentation of the disease appears to have been noted ever since this period.

Early control methods involved a process known as “variolation” which was a process of “scraping” the contents of a smallpox pustule onto an uninfected individuals arm or even inhaling the contents. Surprisingly, this early inoculation process, although it did cause the development of symptoms, did result in a lower death rate than those who contracted the virus naturally.

Edward Jenner is widely credited with introducing the first vaccine against smallpox after observing that milkmaids who had developed cowpox did not exhibit any symptoms of smallpox after variolation in 1796. After (quite unethically, yet successfully) experimenting with this idea on his gardener’s 9 year old son, the basis for immunizations was born, leading us to eventually use the vaccinia virus to successfully eradicate smallpox throughout the world. Jenner inoculated the young boy with scab contents of an individual with cowpox (causing him to develop this milder disease) in which he later followed by exposing the boy to pustule contents of a smallpox patient. To Jenner’s amusement, the boy did not develop smallpox after successful exposure to the cowpox virus.

Transmission

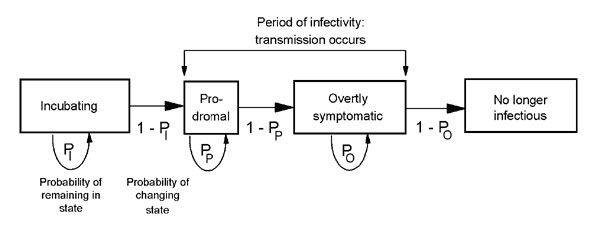

When discussing the transmissibility and epidemiological aspects of smallpox, it is important to understand the various stages and extents of the virus as compiled below by Halloran et al.

The transmission of smallpox can be relatively comparable to that of the more modern-day SARS virus in that they both are spread by close or direct contact with an infected individual or objects. The virus is also capable of being contracted by airborne virus particles. Both of the viruses also have high mortality rates and are known to spread more easily/frequently in hospital and household settings. Transmission modeling of this virus is of particular interest in regards to worst-case scenario preparations (in the event of a smallpox bio-terrorism release). The schematic below from Meltzer et al., produced in 2001, models the person to person transmission of smallpox throughout the stages of the disease.

Various publications have focused on mathematical modelling to predict possible public health measures in the event of a deliberate release of the virus including mass vaccinations, isolation measures, contact tracing with quarantine and vaccination of contacts, as well as ring vaccination around infected individuals. The ring vaccination concept, according to the CDC, “includes isolation of confirmed and suspected smallpox cases with tracing, vaccination, and close surveillance of contacts to these cases as well as vaccination of the household contacts of the contacts”.

Groups have previously utilized the Markov chain model, stochastic simulation of smallpox in a set population focusing on timely mass vaccinations, as well as computer stochastic simulations that stressed the importance of contact tracing and isolation. Others have used a stochastic model predicting that the prior vaccination of healthcare workers might be beneficial.

Castillo-Chavez et al. incorporated the important variable of transient populations on transmission dynamics of smallpox in a more intricate model that I believe should certainly be considered in today’s global culture of highly prevalent travel and migratory tendencies. This group stressed that locally-based control measures would not be sufficient and global policies and approaches to an outbreak would need to occur. Studies focused on strategies to contain local outbreaks after their detection show that timely interventions with vaccination and contact tracing are able to halt transmission. Grais et al. even explored the effectiveness of instituting air travel restrictions as a control measure in the event of a smallpox release.

It was quite interesting to note that most publications I studied for this review were published shortly after the terrorist attack against the U.S. on September 11th, 2001. The years following this compromise on our nation’s safety obviously had (and continues to have) a drastic effect on our understanding and risk perception of potential threats to our public health.

While all this literature is an imperative piece to the puzzle in understanding our ability to predict the outcomes of a smallpox bio-terrorism incident, the aspect of human behavior and our individual propensity to change behavior rapidly must certainly be contributed to this research as examined in the paper by Del Valle et al. Below, this group’s extensive compartmental model taking into account people’s normal contact-activity levels, assuming that their levels are normal before an outbreak and remaining normal until notified that smallpox has arrived in their own community.

The compartmental model visualized in Fig. 7 of smallpox designed by Gonçalves et al. in 2013 incorporates the imperative factor of human mobility patterns.

The figures above provide insight into how much effort has been put forth regarding transmission modelling of the smallpox virus in the case of its use as a bio-terrorism agent; this topic has been, within the past two decades and continues to be, well researched in light of the terroristic threats our country has received. The study of the chain of pathogen transmission from person to person, behavioral and social aspects, as well as the pandemic risk in relation to human mobility/travel patterns have been explored. It should also be noted that almost all of the control methods discussed require a certain medical and public health infrastructure/presence that is not available in all countries. While wealthier and more advanced nations may have the means to control the spread of the disease within their own borders, this is rarely the case in regards to pandemic outbreaks as researchers stress the mobility habits of human beings. Furthermore, due to the prodromal period of the disease, infection would surely spread internationally before officials and healthcare workers are alerted to enforce containment strategies. One particularly concerning factor is the eventual total lack of herd immunity, as previous generations that received the, now, discontinued vaccine are continuing to age.

A key factor essential to the assessment of this risk is Ro, (the basic reproduction number) or the average number of secondary cases infected by each primary case.

R0 has been used to evaluate the severity of an outbreak and the strength of the interventions necessary for control. It is generally accepted that if R0>1, the outbreak generates an epidemic, and if R0<1 the outbreak becomes extinct. The Ro value has been shown to widely vary from historical outbreak accounts, being between 3.5 and 6 before a Nigerian outbreak in 1967 documented to have an Ro value between 4 and 10. This, along with other peer-reviewed literature, poses the concern that Ro may fail at accurately representing a reliable epidemic threshold. Ro should be carefully calculated utilizing many different data (perhaps contact tracing along with previous population level epidemic data and ordinary differential equations) to predict possible transmission mechanisms of a possible future epidemic at the individual level. With this information, I do follow the belief that a smallpox introduction into our population could yield a reasonably rapid epidemic before the intervention of public health implementations. This due, in part, to minimal residual herd immunity since the cessation of smallpox vaccination, the ability for a patient to be infective up to three days prior to the onset of the rash, along with the ease of transmission of the virus from person to person, especially in modern hospital settings, and the basic challenge of targeted vaccination models.

While this is no joking matter, I’ll have someone else leave us on a good note here, because after all, we should celebrate our world’s victory over this disease!

“I was nauseous and tingly all over. I was either in love or I had smallpox.” -Woody Allen

We know now that Woody was probably in love rather than coming down with smallpox, although this may have been a valid thought coming from a teen-aged Woody for those times. And thank God he wasn’t a victim of this horrid disease – he may then have never written one of my favorite movies 😉

Sources

Breban, Romulus & Vardavas, Raffaele & Blower, Sally. (2007). Theory versus Data: How to Calculate R0?. PloS one. 2. e282. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000282.

Burke, Samuel & Epstein, Joshua & Cummings, Derek & Parker, Jon & Cline, Kenneth & Singa, Ramesh & Chakravarty, Shubha. (2006). Individual-based Computational Modeling of Smallpox Epidemic Control Strategies. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 13. 1142-9. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2006.tb01638.x.

CDC; Journal: Emerging Infectious Diseases Article Type: Research; Volume: 7; Issue: 6; Year: 2001; Article ID: 01-0607 DOI: 10.321/eid0706.0607; TOC Head: Research

Costantino, Valentina & Kunasekaran, Mohana & Chughtai, Abrar & MacIntyre, Chandini. (2018). How Valid Are Assumptions About Re-emerging Smallpox? A Systematic Review of Parameters Used in Smallpox Mathematical Models. Military Medicine. 183. 10.1093/milmed/usx092.

Castillo-Chávez, Carlos & Song, Baojun & Zhang, Juan. (2003). An Epidemic Model with Virtual Mass Transportation: The Case of Smallpox in a Large City. 10.1137/1.9780898717518.ch8.

Del Valle, Sara & Hethcote, Herbert & Hyman, James & Castillo-Chávez, Carlos. (2005). Effects of Behavioral Changes in a Smallpox Attack Model. Math Biosci. 195. 228-251. 10.1016/j.mbs.2005.03.006.

Eichner, Martin & Dietz, Klaus. (2003). Transmission Potential of Smallpox: Estimates Based on Detailed Data from an Outbreak. American journal of epidemiology. 158. 110-7. 10.1093/aje/kwg103.

Gani, Raymond & Leach, Steve. (2002). correction: Transmission potential of smallpox in contemporary populations. Nature. 415. 1056-1056. 10.1038/4151056a.

Gonçalves, Bruno & Balcan, Duygu & Vespignani, Alessandro. (2013). Human mobility and the worldwide impact of intentional localized highly pathogenic virus release. Scientific reports. 3. 810. 10.1038/srep00810.

Grais, Rebecca & Ellis, J & Glass, Gregory. (2003). Forecasting the geographical spread of smallpox cases by air travel. Epidemiology and infection. 131. 849-57. 10.1017/S0950268803008811.

Hall, Ian & Egan, Joseph & Barrass, I & Gani, R & Leach, S. (2007). Comparison of smallpox outbreak control strategies using a spatial metapopulation model. Epidemiology and infection. 135. 1133-44. 10.1017/S0950268806007783.

Halloran, M & Longini, Ira & Nizam, Azhar & Yang, Yang. (2002). Containing Bioterrorist Smallpox. Science (New York, N.Y.). 298. 1428-32. 10.1126/science.1074674.

Herfst, Sander & Bohringer, Michael & Karo, Basel & Lawrence, Philip & Lewis, Nicola & Mina, Michael & Russell, Charles & Steel, John & de Swart, Rik & Menge, Christian. (2017). Drivers of airborne human-to-human pathogen transmission. Current Opinion in Virology. 22. 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.11.006.

https://www.1843magazine.com/features/rewind/the-original-antivaxxers

https://www.amnh.org/explore/science-topics/disease-eradication/countdown-to-zero/smallpox

https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/transmission/index.html

Kaplan, Edward & Craft, David & Wein, Lawrence. (2003). Analyzing bioterror response logistics: The case of smallpox. Mathematical biosciences. 185. 33-72. 10.1016/S0025-5564(03)00090-7.

Meltzer, Martin & Damon, Inger & Le Duc, James & Millar, J.. (2001). Meltzer MI, Damon I, LeDuc JW, Millar JD. Modelling potential responses to smallpox as a bioterrorist weapon. Emerging infectious diseases. 7. 959-69. 10.3201/eid0706.010607.

Milton, Donald. (2012). What Was the Primary Mode of Smallpox Transmission? Implications for Biodefense. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2. 150. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00150.

Nishiura, Hiroshi & Brockmann, Stefan & Eichner, Martin. (2008). Extracting key information from historical data to quantify the transmission dynamics of smallpox. Theoretical biology & medical modelling. 5. 20. 10.1186/1742-4682-5-20.

Slifka, Mark & Hanifin, Jon. (2004). Smallpox: The Basics. Dermatologic clinics. 22. 263-74, vi. 10.1016/j.det.2004.03.002.

Thèves, Catherine & Crubezy, E. & Biagini, Philippe. (2016). History of Smallpox and Its Spread in Human Populations. 10.1128/9781555819170.ch16.